The steps of caring for the Museum’s tools collection

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Carley Roche, Associate Registrar

February 22, 2024

Introduction

I love movies. From action and comedies to thrillers and romance, I think movies are absolutely fantastic. And when a character works in a museum, library, archive, or cultural heritage field I get a little giddy because I love seeing my profession on the silver screen. Classics like Indiana Jones and National Treasure hold special places in my heart for this very reason.

However, as much as I adore these films, I also find it amusing that they set up museum collection care as a high stakes adventure while diminishing the technicalities of the job responsibilities held by a museum collection specialist, manager, or registrar. Obviously, it wouldn’t be as exciting to see the character Indiana Jones calmly walking out of a cave holding a relic while at the same time filling out the paperwork related to object information, condition reports, and insurance needs. But, I think it is important for people to understand that although caring for a museum collection doesn’t have me running across rooftops or evading enemies (most days) it does take a lot of hard work, overall caution, and patience.

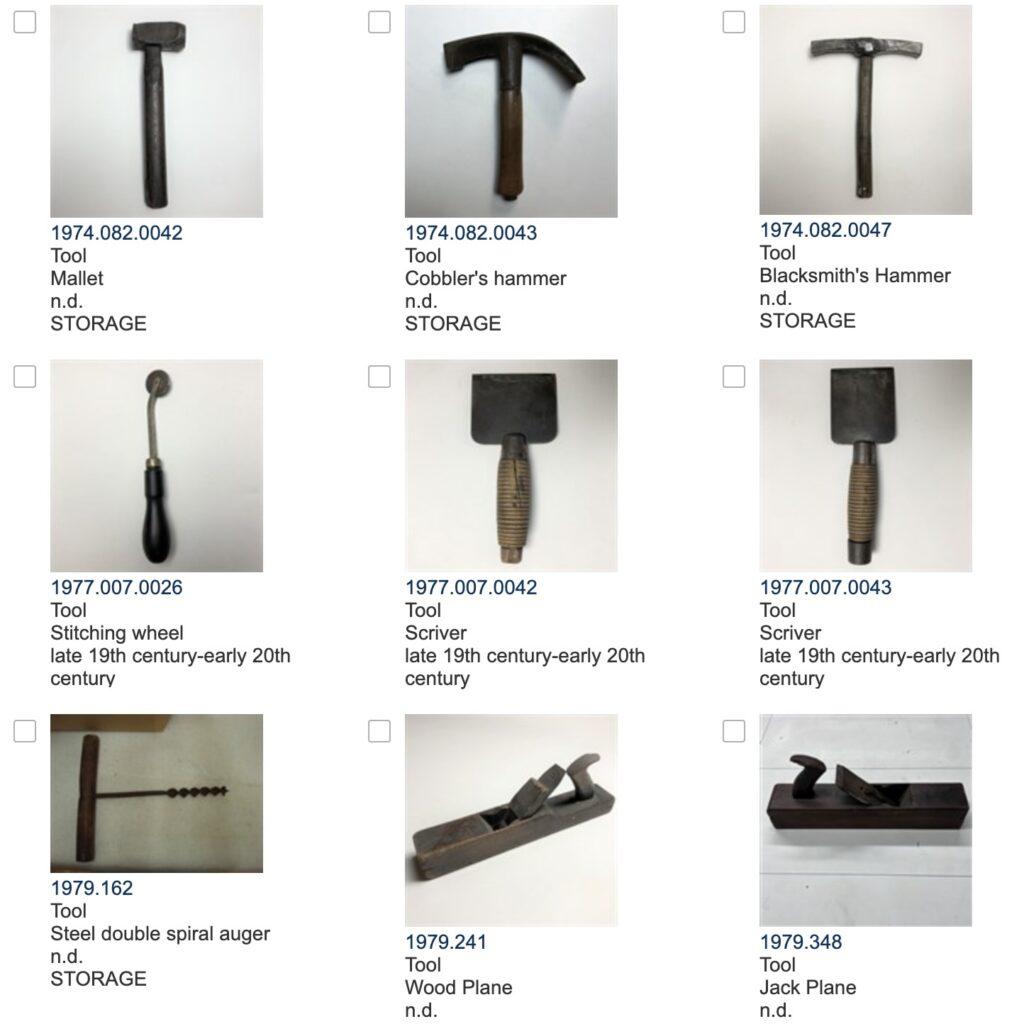

So, when I recently began a rehousing project involving the many tools in the Museum’s permanent collection, I realized this would be a perfect opportunity to share in more detail about general collection care. The South Street Seaport Museum has over 2,500 tools in its collection, and they are made of wood, iron, steel, brass, copper, leather, textiles, ivory, and more. These materials have different preservation needs including ideal temperature, relative humidity, and preservation housing types. The objects themselves are also unique as they were made to be used, so they are typically more damaged than other objects in the collection.

This blog will take you through the steps of caring for tools from the early-19th to the mid-20th centuries, from initial object assessment to final rehousing.

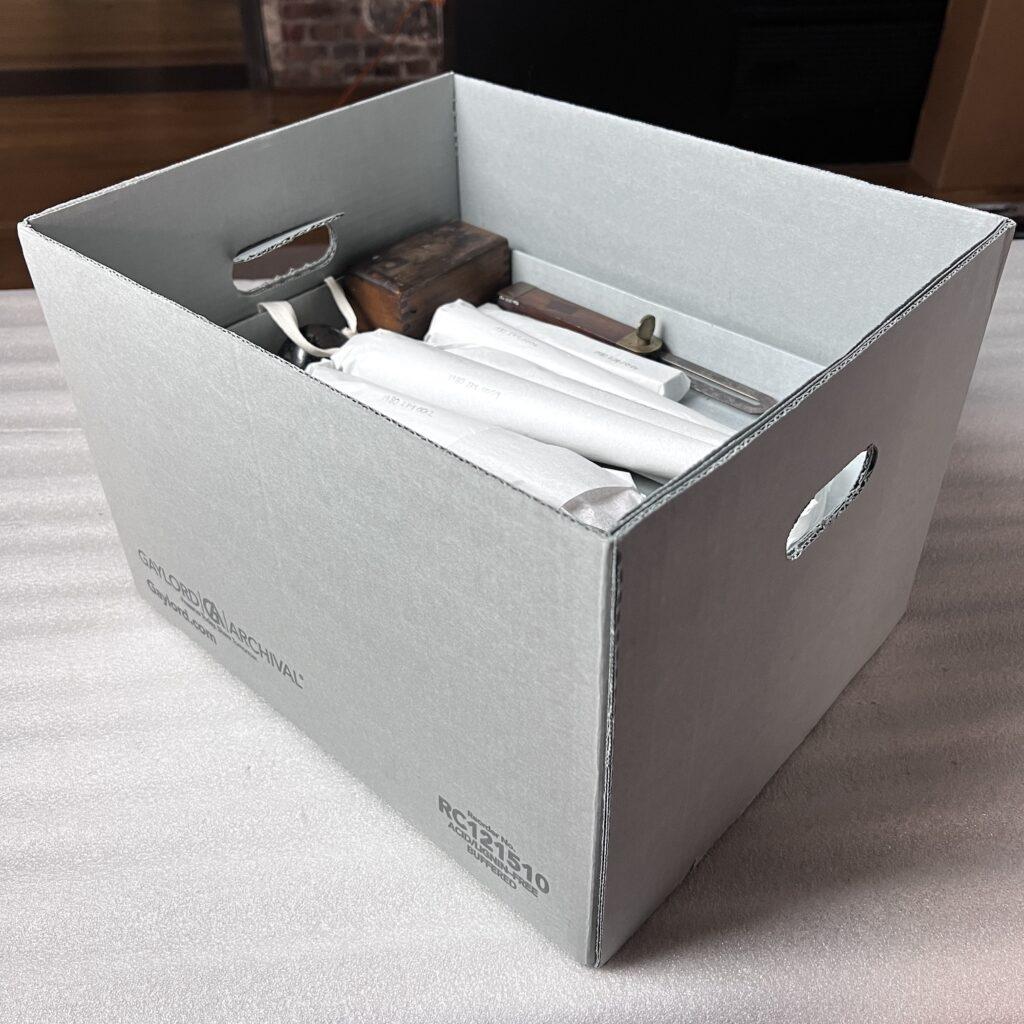

My historical tools assessment and inventory project started in the last few months of 2023 with an initial inspection of the objects including approximately 450 pieces stored in the Museum’s galleries currently inaccessible to the public (which you may have seen in our Year in Review: Collections care activities through 2020 blog post) and 1,500 tools stored in acid-free archival boxes in collection storage. During the inspection, and after checking with my collections and exhibition management colleagues, we decided to rehouse and return to storage all the items that have been stored in the exhibition galleries.

Now we enter the steps of collection care where I think Indiana Jones would have lost a few fans had it been shown on screen: database updates. A museum’s database is a significant tool that gives workers up-to-date information on an object’s location, size, appearance, maker, and research related to historic and cultural connections. Data also includes the history of the object at the museum including provenance, loans, exhibitions, publications, and more recent social media uses. Without an accurate inventory and related information in an up-to-date collection management database, a museum cannot know what it holds in its collection, which can limit its public core function.

The first step taken with the tools removed from their platform was placing them in a dedicated subgroup of artifacts on the Museum’s collection management database and condition reporting them.

This simple task tells me, as well as future Museum employees, that these specific tools were removed from the pedestal in a specific moment in time in a specific condition.

With the objects’ new records, I moved on to the next exciting step in this rehousing plan, which is to sort all the removed tools in order of their accession number to be able to match and rehome them with the ones in storage. An accession number is a type of identification that museum professionals use to track objects. It is especially useful for when there are multiple object types that look alike. For example, this tool’s number reads 1986.046.0118. With this, I know that the piece was acquired in 1986, it was part of the 46th donation of that year, and it was the 118th object in that particular donation.

Accession numbers are crucial for museum organization and identification, so in my rehousing plan I noted that I will work on keeping the tools in storage in order of this number as much as possible.[1]Knowing that some tools are too large to fit in a standard archival box this system would not fit perfectly, but knowing that the 1986 year tools are all in a similar location helps us internally for … Continue reading

Now sorted in order of accession number I began to combine tools in one large gallery space to be able to reunite family members by accession number and rehouse them together. During this process I found that many of the previous dimensions were incomplete or hilariously off (several objects listed as over eight-feet long despite fitting in the palm of my hand, and a six-inch ruler listed as 30 inches) so this was an opportunity to correct these measurements and add a weight for the first time. This step is important for both rehousing and display purposes as I now know what type of shelving unit can safely hold the object and, should it go on exhibit in the future, what type of case and mount it would need.

I wish I could dive deeper into all 2,500 objects and the stories they hold in their well-used handles and blades. These are the tools that helped physically build the port of New York, traveled on ships alongside sailors, and aided craftspeople around the world. For now, enjoy a selection of tools that I found to be particularly interesting as I worked through this project.

Simon Douglas’ Blacksmith Tools

This first set of tools are an important example of collection care. These blacksmith’s tools were crafted by Simon Douglas (1843–1950), a man born into enslavement in South Carolina, who freed himself by joining the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865). After surviving the war, he settled in Fairview, New Jersey, where he worked as a blacksmith with these very tools.

The material of these tools—called tongs—is iron, which is especially prone to rusting. Iron objects can be in an active or inactive state of corrosion with the difference coming down to the stability of the object.

As you can see in the detailed images, these 19th century tools do have a noticeable reddish-orange color to them, but the tongs themselves are not deteriorating, meaning they are in an inactive state of corrosion.

The goal is to monitor the corrosion rates with regular condition reports and to keep dust, dirt, and water away from the surface of the tools as these can cause increased rates of rusting.

“Simon Douglas’s Blacksmith Tongs”, 19th century. Gift of James R. Crane, Sr. 1974.037

So how does one clean and care for an object when it is known that there is expected damage? First is monitoring the environment of our storage spaces. The process of corrosion occurs more slowly in cool dry air, so having environmental loggers throughout storage to track relative humidity and temperature allows me to ensure the Museum’s storage areas meet the requirements for best preservation practices. Every day I record the readings from the loggers and if anything spikes I investigate to see if there are any issues I can quickly resolve or if I need to contact our Facilities team to address the opportunity further.

Next is knowing how to clean iron objects. With the need to prevent the accumulation of dust and dirt in order to avoid active corrosion, it is important to clean the tongs with a HEPA vacuum regularly. HEPA stands for high efficiency particulate air [filter], which the Environmental Protection Agency states, “can theoretically remove at least 99.97% of dust, pollen, mold, bacteria, and any airborne particles with a size of 0.3 microns.”[2] What is a HEPA filter? Using a bristle-tip attachment, I use a low suction setting to slowly move the HEPA vacuum across the surface of each tool. Careful to avoid completely removing sections of inactive rust—as this can cause disfiguration of the original metal beneath—I focus my attention on removing any dust particles I may find.

It is repetitive slow work, but it is meaningful to keep the history of Simon Douglas alive.

Lowentraut Adjustable Wrench

This next object seems exceptionally ordinary as it is one of 100 wrenches in the Museum’s collection. But if you look closely on the fixed jaw of this tool you will see a maker’s mark that reads, “Lowentraut Mfg. Newark, NJ.” The Lowentraut Manufacturing Co. was founded by Peter Lowentraut (1836–1910), the third of seven children. Originally from Hesse-Darmstadt, Germany, the family once held high social standing but was forced to emigrate to America after Peter’s older brother, Frederick W., insulted the Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt at a party. On Christmas in 1851, the family landed in New York City to start their new life.

“Lowentraut Adjustable Wrench” May 21, 1901 (patent date). Gift of Mr. Arthur Steinberg 1980.274.0048

Peter married and became a U.S. Citizen while living in the city. He and his family spent time in Bloomington, Illinois before eventually settling in Newark, New Jersey in 1864. It was here where he started Peter Lowentraut & Co. sometime between 1869 and 1871. Peter was extremely innovative and received several patents related to wrenches including the self-adjusting wrench and a combination wrench-brace. This characteristic, combined with the ice skating craze of the late-19th century, the company found great success leading to the business being incorporated as Lowentraut Manufacturing Co. in 1899. Peter ran his business until his death in 1910. Afterwards, his widow, Anna, took over the business and re-incorporated in 1914. The company was sold in 1920 to the F.D. Kees Manufacturing Co. and relocated to Beatrice, Nebraska.

The story of Peter Lowentraut is so rich with details it is difficult to narrow down to a short paragraph. This is the same for so many immigrants who came to America and began new lives, opened businesses, and started families here. Peter’s story just happens to be kept safely preserved in an adjustable wrench in the Museum’s collection. It has now become my responsibility to ensure this tool is safely cleaned, housed, and generally cared for, but I immediately notice one issue that can throw a wrench in these plans (pun intended): this object is made of two different materials.

When an object is made out of a single material it is easy to understand its overall basic needs. But when you add a second or third material you begin to encounter some difficulties related to preservation guidelines. In this case, the tool’s handle is made of wood while the body is made of steel. These two mediums require different preservation needs, so finding that balance can be a process. Wood is an organic material while steel is a man-made alloy of iron and carbon. Wood can decay naturally and within museum storages due to physical, chemical, and biological deterioration; steel is prone to corrosion caused from moisture, airborne pollutants, and salts and oils from skin contact.

With all of these factors in mind, the first common ground that can be reached is temperature and relative humidity. Both wood and steel are prone to decay when in contact with moisture, so a lower temperature and humidity is suitable for both materials. Steel does not rust beneath a relative humidity of 15%, but wood can lose important natural moisture structure below 25%.[3]National Park Service, Curatorial Care of Metal Objects.

Most importantly, the temperature and relative humidity should not fluctuate, so a steady relative humidity above 25% but below 65% (too much moisture) is ideal for this particular wrench.[4]Northern States Conservation Center. Relative Humidity and Temperature.

Now that the environment is settled for the wrench I have to actually handle it to move it into storage. Both wood and steel are vulnerable to the natural salts, oils, and moistures of my hands, which can cause corrosion, stains, and fast-track decay. Wearing nitrile gloves protects these materials from the natural pollutants of my hands, so it is imperative I wear them at all times. Learning proper object handling techniques also allows for safe movement of objects and less risk of scratching or denting of objects. If I am ever in doubt of my physical capabilities to handle an object on my own, I can share the weight with another trained employee or use a moving cart. Carts are also useful when transporting multiple objects at once.

Thankfully a tool made of steel and wood is common, so this type of mixed-material object has many case studies supporting proper preservation techniques. For more complex objects it is important to take the time to carefully research individual material needs first and then determine a safe common ground for long-term care. Again, it is slow work that takes a lot of care and patience to properly handle and house collections objects, but this needed research time is worthwhile to ensure an international connection found in a wrench can be told nearly two centuries later.

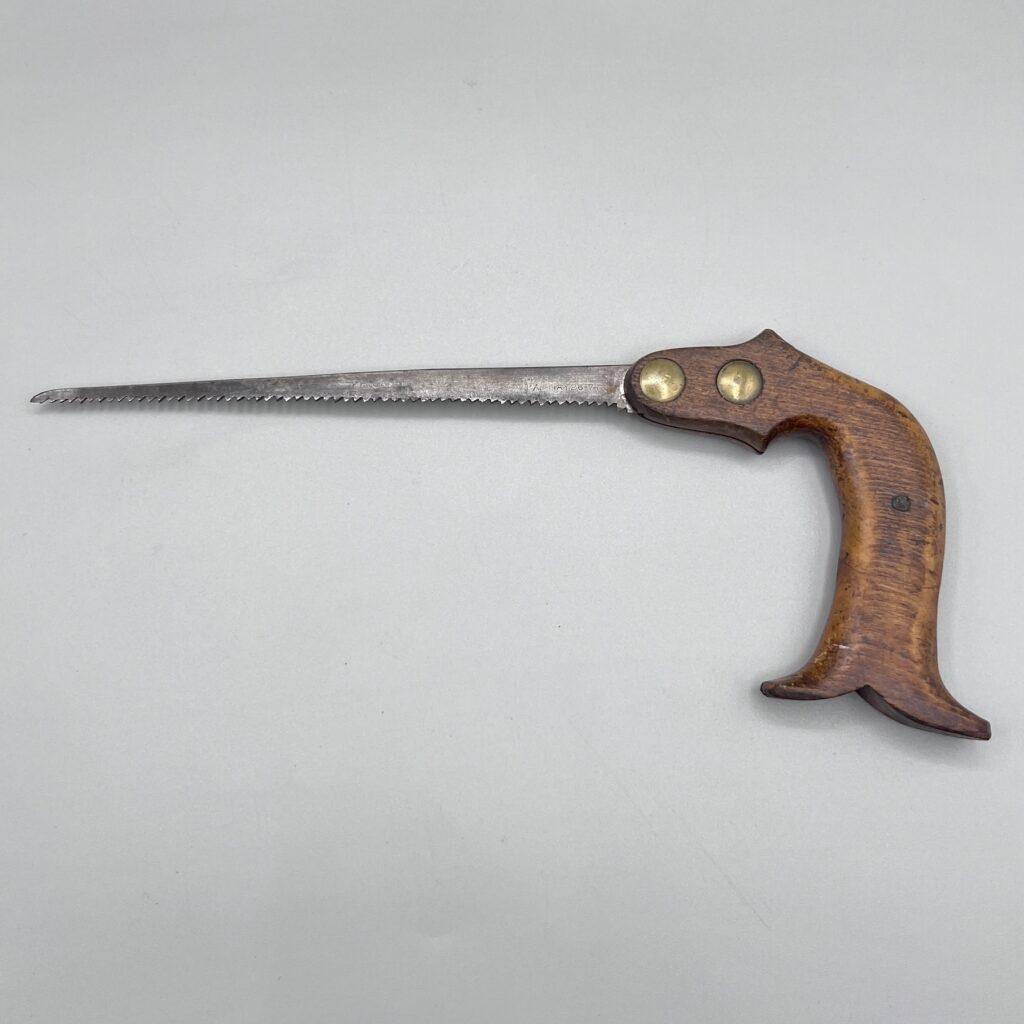

Saws

Over the past few weeks, I have cataloged and handled hundreds of tools to be rehoused in storage. Although it can be repetitive work, it can highlight connections and similarities within the Museum’s collection. For example, while working with multiple types of saws, I noticed a manufacturer appearing again and again, both printed on the tools themselves and in the Maker database: Henry Disston & Sons. As this maker continued to pop up in my work I took a moment to look further into them.

Left: Detail of “Double edged Disston tree saw” n.d. Gift of Mr. Arthur Steinberg 1980.274.0076

Right: Detail of “Hand Saw” n.d. Gift of Mr. Arthur Steinberg 1980.274.0078

Henry Disston (1819–1878) emigrated with his father to Philadelphia from Tewkesbury, England in 1833. Shortly after their arrival, Henry’s father passed away leaving the young boy to attain an apprenticeship with Lindley, Johnson & Whitcraft, local saw manufacturers. In 1840, Henry opened his own saw shop after the apprenticeship business failed. He found great success by incorporating crucible steel into his saw blades. In 1855, Henry opened the first mill in the United States solely devoted to producing steel for saws. His sons, Hamilton (1844–1896) and Albert (1849–1883), joined the business a decade later leading to the company Henry Disston & Sons. The company remained within the Disston family’s control until 1955 and still remains active today as Disston, Inc.

It is incredible how much history and innovation can be found within similar objects in the collection. And that’s the important distinction here—these are “similar” objects, all within the same tool-type family of saws, but not quite the same. The Museum cares for multiple types of saws: ice, keyhole, back, tree, pull, hack and even bone! Although some of these saws may share a maker, their distinct physical characteristics require different titles and identifications for cataloging. Imagine the headache and confusion of trying to sort through an entire collection database of “saws” when you are specifically looking for an ice saw instead of a keyhole saw. This is where the standardized object classification system of nomenclature comes into play.

Left: “Keyhole saw” May 26, 1874 (patent date). Gift of Mr. Arthur Steinberg 1980.274.0074

Center: “Bow saw with steel handle” n.d. Gift of Anna Marie and Joseph Brownson 1983.099.0132

Right: “Ice Saw” n.d. Gift of Arthur D. Steinberg 1986.046.0331

Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging was first introduced by Robert G. Chenhall (b. 1923) in 1973 to identify and classify man-made objects in cultural institutions across the United States and Canada. Since the first publication, there have been three revisions to this system, the latest published in 2015, with updated information given new historical and cultural context. Nomenclature provides consistent and controlled vocabulary for museums across North America to search for and group objects by their function within their collections. It places an object into a category, class, and sub-class and within this system there is a hierarchical organization that arranges the object into primary, secondary, and tertiary object terms. These terms are not always used, but they do allow for more precise categorization when necessary.

With approximately 15,000 object terms in the most recent publication, nomenclature provides consistent and precise classifications. Using these terms we can understand the differences between related objects, which allows us to provide clearer information for internal and external research, helps us prepare for programs and exhibitions, and helps us to easily track and group our collections.

Conclusion

The tool collection I have been working with has approximately 2,500 objects. Understanding the preservation needs of each object—from its internal structure to its storage environment—takes a lot of time and careful consideration. Extrapolate these factors to the Museum’s collection of over 28,000 objects and 55,000 historic records and you begin to realize all of the effort that goes into caring for a collection of this size.

Although my day-to-day work does not have me racing against time and villains to seek out a lost ark or plotting to steal the Declaration of Independence in search of a hidden treasure map, I am busy cleaning, cataloging, and handling objects on top of monitoring their environments—tasks I can’t imagine Indiana Jones doing. Although it doesn’t sound as exciting as what we see in the movies, I think the stories that come from museum collection care work are grand enough for the silver screen.

Additional Resources and Readings

Canadian Conservation Institute, “Preventive Conservation Guidelines for Collections” September 2018.

National Park Service, “Museum Handbook, Part I: Museum Collections” 2023.

American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, “Caring for Treasures” 2024

“Remembering state’s last Civil War veteran” by Silvio Laccetti, The Jersey Journal February 11, 2018.

“Care and Cleaning of Iron” by Judy Logan, 1987. Revised by Lyndsie Selwyn, 2007.

“The Disston History Collection” Hagley Museum and Library, 2015. Revised by Laurie Sather, 2022.

“Peter Lowentraut–New Jersey Tool Maker” by Stan Morgan. The Tool Shed, June 2017.

“Recognizing Active Corrosion” by Judy Logan, 1988. Revised by Lyndsie Selwyn, 2007.

“Newark: The city of industry” by Newark Board of Trade, 1912.

“Nomenclature for Museum Cataloging”, January 2024.

“Disston & Sons, Keystone Saw Works” Workshop of the World, 2007.

References

| ↑1 | Knowing that some tools are too large to fit in a standard archival box this system would not fit perfectly, but knowing that the 1986 year tools are all in a similar location helps us internally for research and public use purposes. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | What is a HEPA filter? |

| ↑3 | National Park Service, Curatorial Care of Metal Objects. |

| ↑4 | Northern States Conservation Center. Relative Humidity and Temperature. |